By David Berger

Everything in aviation is a trade-off. If you want to carry more load, you won’t be able to fly as far or as fast. If you really want to fly fast you’ll need a skinny wing that won’t like flying slowly, and puny wheels that fold away and don’t like rough surfaces.

If you absolutely must take off and land vertically, you won’t go very fast at all, you won’t carry very much load, you will use tons of fuel, the maintenance costs will cripple you, your false teeth will get shaken out of your gums and, to boot, you’ll get wet when it rains. And if you are so foolish as to want to operate off both land and water, well, the compromises are too many to list here, except… except if you are operating a Seabear.

The Seabear (known as the Chaika in Russian), is a twin-Rotax, composite, four-seat amphibious flying boat. It’s a taildragger, it looks good, it flies good, it flies far, it flies reasonably fast, it carries a good load, it’s spacious, comfortable and performs well on one engine. You can land it on deep snow with the wheels up and, best of all, right in the middle of the panel sits a huge, 1950s Russian aviation clock. There is nothing not to love.

We looked all round the yellow and blue demonstrator, stylishly bedecked with a Russian eagle on its tail, with Dimitri and Valentine and then climbed in, Tom starting off in the right seat. In less than ten minutes we were speeding down the Volga at 300 feet for some touch and goes on a quiet stretch of the river between an island and the shore.

Dmitri doesn’t have much English but, between experienced pilots, the language of piloting doesn’t need many words. Tom and I, both of whom have floatplane experience, had no trouble flying a few touch and goes in this delightful aircraft.

“What’s it like on one engine?” I asked innocently, as we settled on the downwind 250ft after my second touch and go.

“ВОТ! (VORT!)” replied Dmitri, reaching over with his enormous hand to grasp the right-hand throttle and bring it to idle and then feather the prop. The answer is: “Pretty good”.

We were four up with a reasonable amount of fuel and I could get a 300ft per minute climb going, though a little more rudder trim would have been nice.

After my turn at the controls we did a full stop landing and bobbed about for a bit on the river. We climbed out of the capacious rear hatch to stroll up and down the fuselage, pose between the rakish twin tails, wave to passing boats and generally marvel that we were standing on a flying boat floating on the Volga River in Russia, which isn’t something you do every day of the week.

I will not deny that our faith was tested by that trip in the Seabear. By the time we got back to Krasniy Yar airfield, we were high on visions of South Pacific flying boat cruises in the style of C.G. Taylor’s 1950s memoir, Bird of the Islands (read that book if you haven’t already). There we were, two RayBanned aviators on the flight deck (for the Seabear almost has a flight deck), grizzled and taciturn denizens of the skies over remote oceans, our crows-footed eyes scanning the horizon for an eagerly sought landfall, then swooping over the lagoon to a flawless landing in between the coral heads. We shut down and climb out onto the fuselage, just in time to greet the small flotilla of canoes filled with excited locals and splashing, yelling, smiling children. Tokelau, Palmerston, Ontong Java, Mangareva, the Tuamotus: the magical lagoons of the far-flung Pacific called to us, enticing us with their siren song.

We cast withering looks towards the 185: how much could we get for that ugly, cramped, noisy tin of Spam anyway? How much would a new Seabear cost? How would we fit it out? We even got as far as the paperwork ins and outs of operating an experimental aircraft internationally.

But, the day was coming to a close and our compulsive checking of the weather brought us back to earth with a jolt. Valentine had invited us to his summer house on the Volga the next day, but unless we left soon the weather was going to keep us in Samara until after the weekend and we did not have the time for that, so we regretfully had to decline.

The night was spent in the garishly painted Dom Pilota, the airfield’s accommodation for visiting pilots. The next day we were up early, mulling over freezing levels and clearances and liaising with Evgeny, our flying-in-Russia fixer, before finally departing for our next destination, Ekaterinburg in the Ural mountains, midmorning. The flight was uneventful, IFR, in and out of cloud layers all the way. Tom was flying and was in his own space as usual, in tune with the machine. He doesn’t talk much. Even on a long flight he will be silent for hours at a time. He listens to music, caresses the control column and occasionally fiddles with the avionics, thinking, always thinking. The flight passed for me in a pleasant, smooth daze.

Ekaterinburg has a large international airport, its vast expanses of smooth concrete seeming absurd after Krasniy Yar’s manicured grass and Beketovka’s chaos of rubble, potholes and trees. We were directed by a follow-me car to a very specific patch of apron, which looked like any other patch of apron, and shut down. The driver indicated that our fuel would be coming and then sped off. We waited. After about half an hour, another small car approached and stopped. Two young women got out and approached, giggling. They had a little English: they were from the airport’s PR department and they wanted to interview us so they could put out a story about our trip on Instagram. Why, we would be delighted!

A series of the usual questions later, we were reminded we were in unreconstructed Russia by their final gambit: “Which country,” pause for giggles and knowing looks, “which country on your trip did you think had the most beautiful women?!” Collapse into gales of laughter. Reader, you and I know there is only one answer to such a question, and we gave it, and afterwards all was well.

Not long after the PR girls left, a truck turned up with the usual two pristine blue and white drums of fuel, which we proceeded to hand pump. Warning to all prospective trans-world aviators: you could not do this trip without a hand pump.

We were escorted to the very sparkly terminal, where, miraculously, someone was waiting for us. A smartly dressed man of about thirty, with almost no English, had been sent to look after us. He was a friend of Evgeny’s business assistant, but we didn’t get much more information than that. Anyway, he was extremely kind, showed us all round the city, which had a level of affluence we had not come across in Russia so far, and a startling line in street art. Dinner was in a bar he co-owned, to the usual background of Russian techno-pop and we were once again struck by the extraordinary kindness of so many people towards these anonymous travellers from overseas.

Our destination the next day was the small airfield of Maryanovka, about 50km west of the mid-Siberian city of Omsk and about 450nm east of where we were. Omsk is now known in the west as the site of the hospitalisation of the Russian opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, following his inflight poisoning, but at the time all we knew about it was that it rhymed amusingly with the nearby city of Tomsk. There, we would be looked after, we were told, by a mysterious character called Malabar. Everyone knew Malabar and everything would be sorted out by Malabar. Oh-kaaay.

The weather was not great, and we were particularly concerned about quite low freezing levels, so we tried to file for a suitably low altitude. Each time Evgeny tried, however, the flight plans were rejected. Eventually, the reason became clear. In Russia, we were limited to socalled international airways on which the area controllers of course speak English. Unfortunately, our route took us over the city of Kurgan which has quite a large area of low level controlled airspace around its airport and flying through it would mean, therefore, that we had to talk to the Kurgan aerodrome controller, who did not speak English.

“Just file higher and request a lower altitude en route if you need it,” said Evgeny. With some trepidation we did, and the plan was finally accepted.

Sure enough, we found ourselves entering icing conditions as we climbed to our assigned altitude and requested lower, which was readily granted by the helpful controllers. We were discussing with each other what would happen as we approached the low level airspace around Kurgan when the controller came on and asked us for a long series of estimates, which we gave him, thanks to the Garmin GTN 750, and these, we surmised, must be for the low level airspace boundaries around Kurgan. We then promptly lost contact with the area controller and so thought we had better call up the Kurgan controller before we entered his airspace unannounced and he scrambled a squadron of MIGs to meet us. After a couple of attempts, contact was made, but he didn’t speak any English. Somehow, though, my schoolboy Russian carried us through – you never know when that stuff is going to come in handy. It appeared he was expecting us, and before long we were through without any trouble and on the other side and talking to the next area controller.

Siberia starts at the Ural Mountains, so east of Ekaterinburg we were officially in Siberia proper. Every glimpse of the ground revealed odd circular lakes, surrounded by marshland. These are kettle lakes, caused by water entering cavities in the ground left by retreating ice, and they are emblematic of the Siberian landscape. Beyond these lakes and forest, there was little to see for mile after mile. Siberia is pretty flat, with huge cities of a million or more separated by vast expanses of wilderness. It has a feeling not dissimilar to Australia: an ocean of land, with sparsely dotted islands of human habitation.

We had been battling a strong headwind the whole way and, since we had done quite a lot of flying in the previous few days, we were keen to get down and have a cuppa and meet the mysterious Malabar. Notwithstanding the charming PR girls of Ekaterinburg, we were also keen to get back to small airstrips. Our destination could not come soon enough.

We could see the large conurbation of Omsk in the distance and were cleared to land on the large grass plain which signified the airfield by the Omsk controller, with instructions to call him on the ground. You are always in touch with a controller in Russia, and always have to have permission to be in the air, unless you are somewhere so extraordinarily remote that the long tentacles of the Russian state have no chance of reaching you, but more on that further east.

The main trans-Siberian highway ran just to the north of the airfield and there was a medium-sized, obviously muddy and poor, village to the south. There were two lines of parked aircraft (including the obligatory pair of AN-2 biplanes) and a couple of hangars, outside which stood a few men looking up at us. A car was racing madly up the strip, evidently doing the Russian equivalent of a ‘Roo run’ (in this case for horses) and we knew this was a place where we would be more at home than at any ‘proper airport’. After an absurdly short landing into the 20knt headwind we taxied back and shut down next to an L29 jet.

The welcoming party treated us like conquering heroes, with huge smiles, big Russian handshakes and much back slapping. The Omsk aircraft spotters club had even come out with their banner to have their picture taken with us. This was the life! Before long, we were ensconced in the cosy night watchman’s caravan, having a cup of tea and waiting for the mysterious Malabar to turn up, the Mr Big of Omsk aviation, the maven of all things aeronautical in central Siberia.

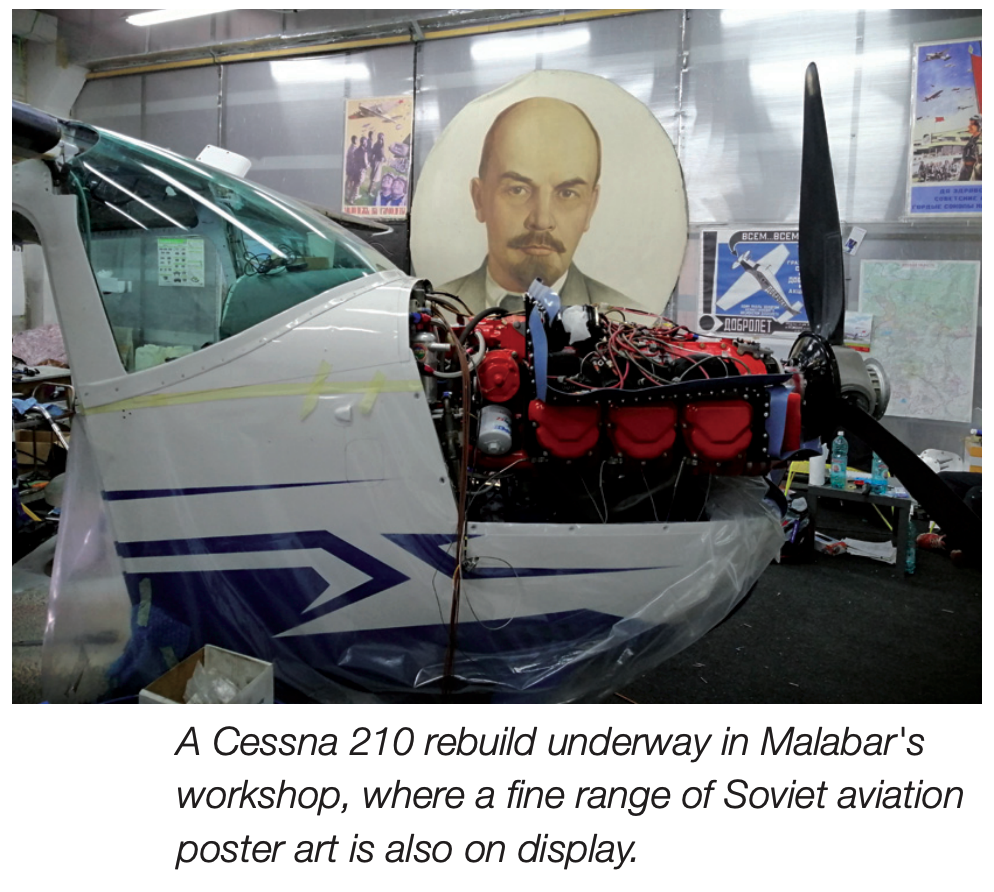

Malabar turned out to be a charming, down to earth fellow. He showed us round the workshop where he was supervising a number of aircraft rebuilds of an extraordinary quality: a Cessna 185, of all things, a 210, a 337, a Lake Buccaneer and others. Apart from the high standards of engineering, the workshop was notable for a wonderful selection of Soviet-era aeronautical posters. It was interesting to talk to these men of my age, all in their 50s, for there was a yearning there. They had all grown up in the Soviet Union and, though they made fun of it, there was also a sense that much ineffable had been lost in the transition to greater personal freedoms: certainty, predictability, law and order, camaraderie, even meaning itself. Perhaps the universal prerequisites for a fulfilled human life are not entirely those we have all been indoctrinated to believe?

Malabar drove us into town with one of the engineers, a former Soviet air force technician, and we talked of aircraft and personalities. The airport manager of our next stop, Gorno-Altaisk, about 450nm east and then south round the tip of Kazakhstan, had been seconded from Omsk airport and was well-known and liked locally, so that was reassuring. We put up at a small, cheap hotel and Malabar took us out to his favourite restaurant, where vodka was drunk and Google Translate, for perhaps the first time in its history, translated the phrase “And now we shall crunch the bones of animals, like small dog,” from Russian into English.

The next morning we caught a taxi back out to the airfield and got packed up and ready to go, when there was, inevitably, a problem with the clearance. Telephone calls back and forth to Omsk Control and Evgeny in Moscow revealed the cause. Though Barnaul Control, whose sector we would have to pass through en route to Gorno-Altaisk, had scheduled an English-speaking controller for us, there was no one English-speaking available at Gorno-Altaisk for our arrival. Could we please, therefore, revise our flight plan to arrive after the tower had closed at 5pm? Certainly we could, and that meant we also had time to nip off with the airfield watchman in his immaculate 1984 Lada to the small cafe on the trans-Siberian highway about ten minutes drive away. Here, alongside long distance truck drivers and taciturn Russian families, we made our first acquaintance with the ubiquitous Laghman soup, a broth which warms and nourishes Russian bellies from the Urals to Vladivostok and beyond.

By the time we got back to the airfield – narrowly avoiding getting the Lada stuck in the mud in the village – it was about 1pm and our flight plan had been approved. We said goodbye to our kind new friends, climbed into the 185 (which we had by now forgiven for not being a Seabear) and set off for Gorno-Altaisk, the Altai Mountains and further adventures on the Mongolian border.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2021 edition of Approach Magazine, the dedicated magazine of AOPA NZ, which is published quarterly.