By David Berger

From Balikpapan on the east coast of Borneo, Broome, on the northwest coast of Australia, now lay less than 1100 nautical miles away. In still air, we would just be able to make it on the fuel in our wings.

Barry and Sandra Payne had done ex- actly that in their absurdly long-legged (and rather faster and more comfortable) Comanche a few days earlier, but we needed another US$2,500 refuelling stop to make it with any degree of safety. (Note to self: for the cost of one refuelling stop in Asia you can install a Turtlepac which will get rid of the need for that stop.)

The 450 nautical mile route south from Balikpapan to Lombok, which we’d planned as our refuelling stop, parallels the Borneo coast for about an hour and a half, then crosses the Java Sea via a few scattered atolls to the eastern tip of the Kangean Islands, from where the vol- canoes of Bali and Lombok become vis- ible above the shimmering haze. Fellow transoceanic pilots will well recognise the feeling of security and comfort which proximity to land gives. While it is, to some extent, justified in a light twin, it is an illusion in a single – but, hey, you might as well enjoy it as not, right?

The first part of the flight was taken up with commenting on the degree of urban development in the region of Balikpapan. At the time of our flight, it had just been announced as the new future capital of Indonesia, to be called Nusantara, due to be inaugurated in 2024. Coming from a country with a tiny population, such as Australia or New Zealand, it is hard to comprehend the sheer press of humanity

in Indonesia. Overcrowded Java, home to the present day and historic capital, Jakarta, has a population of 145 million. Even Lombok, dimensions approximately 40 by 40 nautical miles and with half its area taken up by a 12,000ft volcano, has a population of 3.8 million.

The volcanoes of Bali were visible from far out and before long we were descend- ing along the east coast of Lombok into the international airport. It had been a relaxing three and a half hour flight. Handling via our handling agents at Indoasia was very smooth and we had soon refuelled the aircraft – the last time we would hand-pump an avgas drum on the trip – and were in a taxi heading for a cheapish hotel at Sengiggi Beach, about an hour away.

What can I say? Asian beach resorts have lost their lustre for me since I was last in one in the late eighties, at which time they seemed the height of exoticism and cool. Probably because both they and I have aged, they now seem rather tawdry places, desperately trying to hawk their shoddy wares to an increasingly demanding and intolerant Western tourist throng. But, as unattractive as a holiday destination Sengiggi Beach may be, it was still a welcome location for some tired pilots contemplating the end of their trip. We sat in a beach bar and exchanged emails with the Australian Border Force in Broome while downing a couple of ice cold Bintangs and reflecting that life could have been much, much worse.

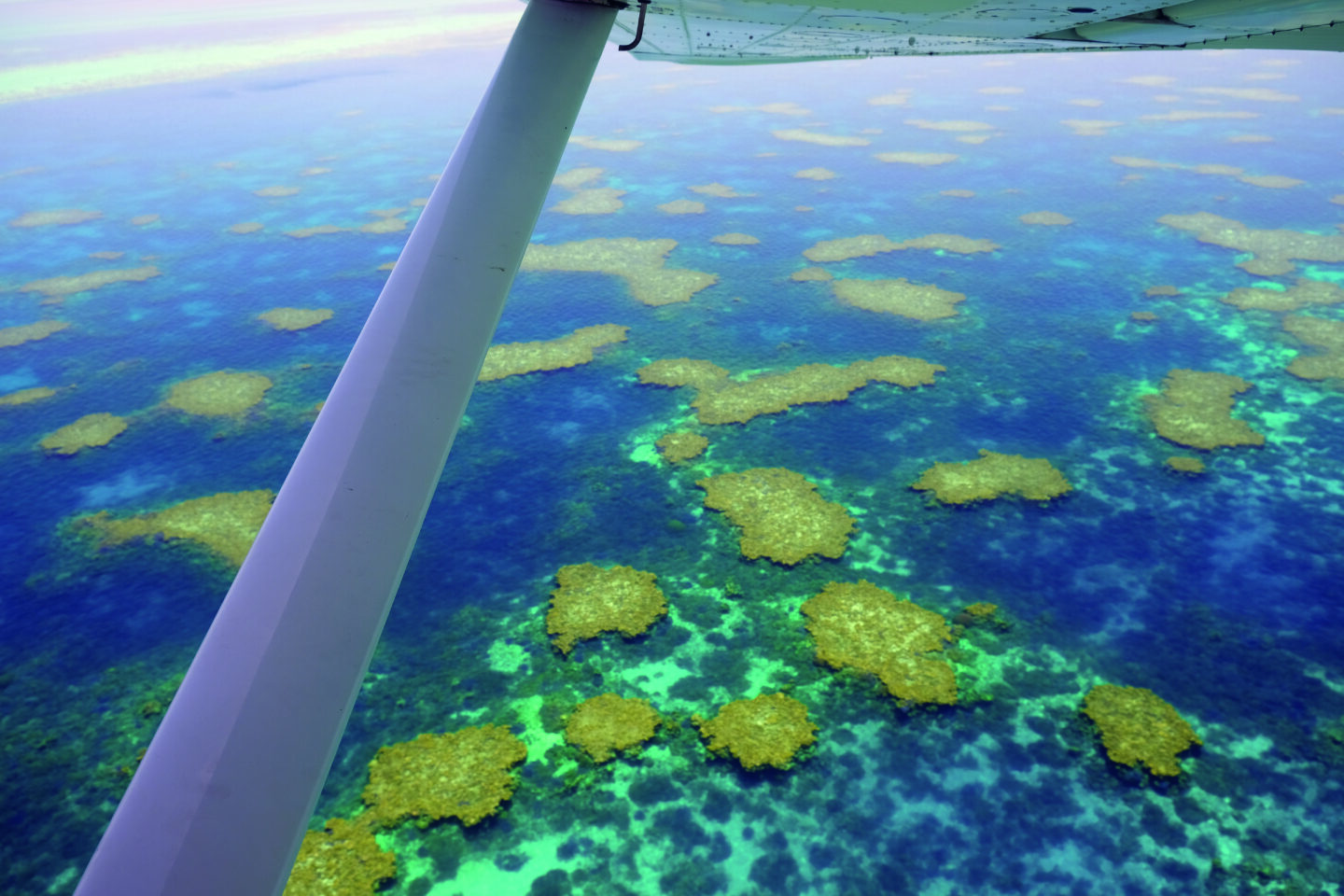

Offshore from Broome, about 150 nautical miles to the west-northwest, lie the Rowley Shoals, a group of three atolls, whose fringing reefs poke the odd tiny sand island above the surface. They represent one of the most pristine marine environments in the world and are the destination for a couple of dive boats working out of Broome. Overflying would only be a small diversion, so we planned a route via the Rowleys.

After a lazy day at Sengiggi, we decamped to an anonymous, modern, depressing hotel near the international airport, where almost nothing worked, Barry and Sandra Payne had done exactly that in their absurdly long-legged (and rather faster and more comfortable) Comanche a few days earlier, but we needed another US$2,500 refuelling stop to make it with any degree of safety. (Note to self: for the cost of one refuelling stop in Asia you can install a Turtlepac which will get rid of the need for that stop.)

The 450 nautical mile route south from Balikpapan to Lombok, which we’d planned as our refuelling stop, parallels the Borneo coast for about an hour and a half, then crosses the Java Sea via a few scattered atolls to the eastern tip of the Kangean Islands, from where the volcanoes of Bali and Lombok become visible above the shimmering haze. Fellow transoceanic pilots will well recognise the feeling of security and comfort which proximity to land gives. While it is, to some extent, justified in a light twin, it is an illusion in a single – but, hey, you might as well enjoy it as not, right?

‘The traveller must learn… that the travel has changed only him…’

The first part of the flight was taken up with commenting on the degree of urban development in the region of Balikpapan. At the time of our flight, it had just been announced as the new future capital of Indonesia, to be called Nusantara, due to be inaugurated in 2024. Coming from a country with a tiny population, such as Australia or New Zealand, it is hard to comprehend the sheer press of humanity in Indonesia. Overcrowded Java, home to the present day and historic capital, Jakarta, has a population of 145 million. Even Lombok, dimensions approximately 40 by 40 nautical miles and with half its area taken up by a 12,000ft volcano, has a population of 3.8 million.

The volcanoes of Bali were visible from far out and before long we were descending along the east coast of Lombok into the international airport. It had been a relaxing three and a half hour flight. Handling via our handling agents at Indoasia was very smooth and we had soon refuelled the aircraft – the last time we would hand-pump an avgas drum on the trip – and were in a taxi heading for a cheapish hotel at Sengiggi Beach, about an hour away.

What can I say? Asian beach resorts have lost their lustre for me since I was last in one in the late eighties, at which time they seemed the height of exoticism and cool. Probably because both they and I have aged, they now seem rather tawdry places, desperately trying to hawk their shoddy wares to an increasingly demanding and intolerant Western tourist throng. But, as unattractive as a holiday destination Sengiggi Beach may be, it was still a welcome location for some tired pilots contemplating the end of their trip. We sat in a beach bar and exchanged emails with the Australian ready for an early departure next day.

I was pilot in command for this leg and, due to my instrument rating deficit, we had to file VFR. After an uneventful departure, HF communications soon faded out, more through lack of interest from Indonesian ATC than lack of reception, and we were left to the reverie of our own thoughts on the 650 nautical mile trip in the smooth air over the sparkling ocean. My thoughts, WW2 tragic that I am, drifted towards the desperate days at the end of February and the beginning of March 1942, when this very patch of airspacehad been a hive of frenetic activity.

The Japanese advance, already rapid, now stepped up even more following the loss of most of the Allied naval fleet in the disastrous Battle of the Java Sea on 27th February, and the chain of islands from Java to Lombok were full of desperate Allied civilians and servicemen trying to escape to Australia, with Broome the nearest suitable bolthole. A revolving door ferry of overloaded landplanes and Dornier and Catalina flying boats brought out as many as they could and, on the morning of the third of March, up to fifteen

flying boats lay at anchor on the turquoise waters of Roebuck Bay, packed with the passengers they had brought in the night before, who had remained on the aircraft as there was no accommodation in town. Just after 9am a dozen Japanese Zeros came roaring in from their base on Timor and spent an hour strafing the flying boats and the airfield. It was carnage. As many as a hundred and fifty died in the raid and a B24 Liberator was shot down, along with a KLM DC-3 carrying not only escapees from West Java, but a cargo of diamonds. Piloted by a flamboyant White Russian called Smirnoff, it made a forced landing on the beach about 75 nautical miles north of Broome and, after an epic four days, the survivors were eventually rescued. The only sign of the diamonds, however, was a tiny trickle here and there over the next several years. The bulk of them were never found.

As usual when we flew over the ocean, we were monitoring Channel 16 on the panel-mounted marine VHF and we got a surprise as we descended through about 4000ft towards the Rowley Shoals: an Australian Border Force Dash 8 was overhead and interrogating each of the three dive boats at the Shoals as to their names, origins, souls on board, etc.

We thought it best to announce our presence, which we did on the marine frequency, followed by which there was a long, suspicious pause before they asked us to change to an aviation frequency and then grilled us in the same, rather officious manner. The Australians take the security of their northwest maritime border very seriously.

After a little low level zooming around the Rowleys, and oohing and aahing at the lovely blue and green colours, we climbed back up to five thousand feet and set course for Broome. I have been a doctor at the hospital in Broome since coming to Australia from the UK in 2013 and we have a house there, so it was pretty special to see the fuzzy brown line on the horizon firm up, and to then approach the town from the ocean side for the first time ever. The colours and landscape of Australia were as striking, outlandish and distinctive as ever.

We crossed Cable Beach and joined left downwind for runway 28, taxiing in to the itinerant parking on the northern apron, where Border Force was waiting for us to go through the formalities of entry. I shut the aircraft down and, in homage to HG Tilman, who famously remarked, on conquering the previously unclimbed 26,000ft peak of Nanda Devi in 1936 with his climbing partner, Noel Odell, “I believe we so far forgot ourselves as to shake hands on it”, we did the same.

The cheery chappies from Border Force ran through their formalities very pleasantly and efficiently. Also waiting for us was our welcoming committee: one of my nurse colleagues at work and his infant son! They had been following us on Flightradar 24 and had kindly come to welcome us home. Apart from that, it was just a normal day in Broome and, of course, an anticlimax, as any homecoming after a long trip is bound to be, even one as momentous as this one.

We relaxed in Broome for a couple of days, basking in no glory whatsoever: “Oh, hi, you’re back for another run!” said everyone I met.

“Yes, flew in this time in my own plane from America, via Russia and Lombok, what do you know!”

“Nice. Hey, look, can you swap a shift next week…?” Came the typical reply.

“Don’t I look different? Can’t you see the changes wrought by the extraordinary experience of crossing the world with my son in this tiny gnat of a plane these last ten weeks? Don’t you understand I am not the same person as when you last saw me? Are these experiences and gems of knowledge not etched on my very face? How could you?” I wanted to reply, but didn’t. For the traveller must learn every time the painful lesson that the travel has changed only him, and that the world and the people he left remain unchanged by the events and experiences which have altered him forever. It is for the traveller, alone, to renegotiate his relationship to the world to which he has returned, not vice versa.

The romance of air travel was further punctured when I tried to refuel the aircraft at Broome for a sightseeing flight up the Dampier Peninsula to the Aboriginalrun lodge and airstrip at Cape Leveque. It transpired two out of three ain’t good:

• I had an Australian BP fuel card

• The fuel in Broome is supplied by BP

• The registration on the card was that of my Super Cub, VH-YUP It would require an email to BP head office in Melbourne for permission to refuel the aircraft, either by BP fuel card or credit card, because it had a foreign registration and that registration was not printed on the fuel card. It may take three days to get a reply.

We had bestraddled the turning globe, refuelling from Iqaluit to Ust’Barguzin, from Fukushima to Vichy, from Burgas to Luzon, and nowhere had made a fuss about refuelling, except back here at home in Australia. Nowhere. Reader, please believe me when I say I dropped to the ground. I wailed, I keened. I gasped. I stretched my eyes. I beat my fists. Finally, as I knew it would, the hassle of not refuelling the aircraft started to look a lot more than the hassle of refuelling the aircraft and thereby dispensing with this embarrassing and awkward fool as soon as possible. A phone call was made, attended by frowns and sighs and sideways glances and, lo, soon the aircraft was being refuelled for our joyride.

After our trip up the peninsula to Kooljaman Lodge, since sadly closed, reality was about to intrude. It was now mid October. Having been together continuously for nearly six months, it was almost time for Tom and me to part. After a cardiac life support refresher course in the East Kimberley at Kununurra, to which we were going to fly in N185MW, I was scheduled to return to Broome to work in the hospital while Tom continued on in the aircraft to our home on the east coast of Australia and then to New Zealand, where in late November he was due to start his second season of towing gliders at Omarama.

We had both reached the point where we felt like our nomadic existence was naturally going to continue indefinitely, living from daily leg to daily leg, flying on in this magical state forever, removed from reality and everyday cares, concerned only with the weather, permissions, accommodation and availability of fuel. It felt like the natural order of things… but the truth was that we were almost out of both time and globe to fly around. Not only that, but a bit of cash in the bank account from an actual job was starting to seem like a good idea too.

The trip from Broome to Kununurra was a lengthy and bumpy reminder of what flying in Australia in the hot months is like, with turbulence reaching as high as twelve or thirteen thousand feet. The stress on aircraft and crew can be considerable, especially if, God forbid, you get caught up in any of the fearsome summer build-ups in the Top End, at which point it would be extremely reassuring to look out of your window and see a beefy strut holding your wing in place, such as we had in the 185. It is well worth planning for a pre-dawn departure to get your flying over with as early as possible when the air is bubbling in Australia.

And that was it. At dawn on the second day of my cardiac course, I found myself standing on the ramp at Kununurra, saying goodbye to my nineteen year old son, with whom I had shared so many adventures. Eighty years before, young men of the same age had climbed into similar, but even more powerful machines and gone off to war, many of them never to return, so what was a solo trip across Australia and the Tasman Sea to the southern tip of New Zealand for such a lad?

Next time, in the final instalment of Wrong Way to NZ, we follow Tom from Kununurra to Omarama and encounter a few surprises along the way.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2023 edition of Approach Magazine, the dedicated magazine of AOPA NZ, which is published quarterly.