By David Berger

As far as we are aware, prior to the pioneering crossing of Russia by Norman Surplus and James Ketchell in their autogyros in the northern spring of 2019, no Western light aircraft had ever before crossed Russia from west to east without a Russian navigator on board.

Since about 2015, it has been possible to transit the Pacific coast of Russia from Nome in Alaska to Japan, by way of Magadan on the Sea of Okhotsk, and this was initially our preferred route to fly our aircraft home to Australia from USA.

In the spring of 2019, however, we watched agog as Norman and James forged a route across that vast land in their tiny craft, from Pskov in the west to Provideniya in the east, a distance of over 5000nm. “You know, instead of heading northwest from Colorado up to Alaska, we could just go east, cross the Atlantic, keep going across Russia to Japan, and then turn right and head south. We could go the wrong way home!” This was in May. We planned to leave in mid-July.

By a roundabout route, we soon found ourselves in contact with Evgeny Kabanov. You don’t cross Russia without Evgeny’s help. Evgeny is a warm, gravelly-voiced, laconic businessman from Moscow, who loves aviation even more than you do. He is a fan of the Lord of the Rings and flew his R66 helicopter, as one of a flight of three, from Moscow to New Zealand in 2014. Some people reading this will have met him in New Zealand during that trip.

He has also flown it to the North Pole. His mission in life, through his company makgas.com, is to bring Western aviators to Russia and to open up the country’s flying scene generally.

“Sure, no problem. Just tell me where you want to go and I’ll see if I can arrange it,” said Evgeny. “Anywhere?” “Anywhere.”

I studied Russian at school in England in the 1980s, so was able to spend a while negotiating the various Russian aviation websites, including the AOPA website, which has a map of all the airfields, with details about fuel availability, runways, etc. My eye was drawn immediately to the Black Sea and the Caucasus. I mean, why not? He did say “anywhere”, after all.

Various plans were considered, discussed and shelved. Enter at Sochi, the famous resort on the eastern side? “No, don’t go there. If Putin unexpectedly turns up at his palace, they’ll close the airspace and you could get stuck for a week.” Transit stop through Georgia then north across the Caucasus into Russia? Could do, but could also get stuck waiting for good enough weather to cross the mountains. In through the eastern Caucasus and over to dip our toes in the Caspian Sea in Dagestan? Tempting, but timeconsuming, potentially geopolitically “involved” and we had a lot of Russia to cross in the space of a four week visa.

Anapa looked good, a resort town close to the eastern edge of the Crimean peninsula with customs at the airport and the potential for fuel: “Can we go there?” “Sure.” So, Anapa it was, and that’s how we found ourselves one sunny morning in late August driving north from Burgas city in Bulgaria to the airport at Sunny Beach, from where we were shortly due to launch ourselves five hours east across the Black Sea to Russia. Our escort through the airport was a pleasant young law student from Sofia on his summer job with, naturally, perfect English.

We had soon paid our handling fee in a tiny office in the freight hangar and were walking back out to the aircraft when we saw an airport car driving purposefully towards us. It stopped and the driver asked us to get in and drive over to flight ops. There was a problem with our flight plan. Of course there was. The airway we had flight-planned for took us through a tiny snippet of Turkish airspace and Ankara Control wanted to know the purpose of our flight.

The purpose of our flight? What could this mean? Tom and I looked at each other anxiously and proceeded to overthink it. Were they being cagey about us passing through their airspace into disputed Ukrainian airspace and then on to Russia? Was this actually US military intelligence trying to stop us taking a US-registered aircraft into Russia? What should we say the purpose of our flight was?

The man in flight ops, a dark, hairy fellow with a moustache like a New Guinea caterpillar, looked at us amusedly and barked: “Ferry flight!” Ferry flight it was, then, and after suiting up in our immersion suits for the first time in a while, we were soon climbing out over a shining sea, peppered with a few small cumulus at about 5000ft.

The air was dead smooth at our cruising altitude of 9500ft and we settled into the familiar serene routine of cruising over an ocean. Tom set a mellow Spotify playlist to play through the audio panel and we felt rather special and excited as we gave our position reports in amongst those of the dense stream of heavies far above, their blithely unaware human cargoes sipping coffee and watching movies as they sped to and from the Gulf and points east and west.

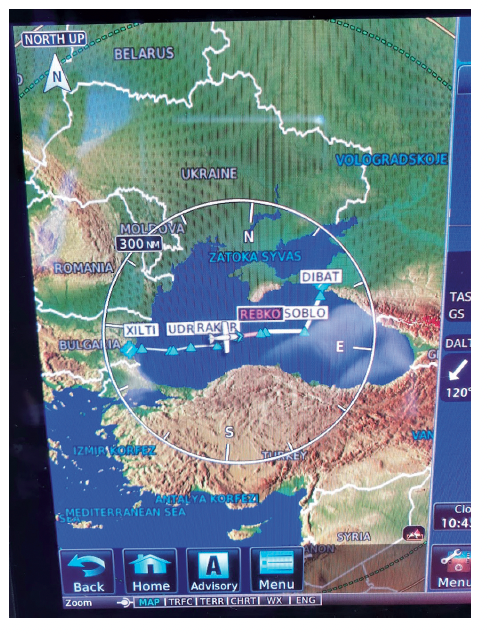

Ankara Control showed no special interest in us and soon handed us over to Odessa Control for the next leg of our flight through Ukrainian airspace. Keen students of global geopolitics will remember the Russian annexation of the Crimea from the Ukraine in 2014, the ongoing war with Russia in the Donetsk region and the shooting down by a missile of MH17 by Russian-backed separatists, or maybe even by Russian troops themselves. As a result of the risk from small arms and rocket fire in the Dnipropetrovsk FIR in the eastern Ukraine, and from conflicting guidance from Ukrainian and Russian controllers in the Simferopol FIR, which extends down to meet Turkish airspace over the Black Sea, various parts of this airspace have been placed out of bounds by the FAA to US-registered aircraft since 2014. This meant that we were not able to take a direct route through the Simferopol FIR to our destination, but had to make a significant dog-leg which added about half an hour to the journey. It also meant that the near constant hubbub of airliners making position reports ceased almost entirely as soon as we entered Ukrainian airspace, leaving only the occasional Ukrainian Airlines flight from Kiev to Odessa to pierce the static.

It was a spooky feeling, knowing that we were almost certainly being observed from a US AWACS plane over Turkey and that the crew would be speculating as to what this US-registered single-engine Cessna was doing on such an odd flight. Perhaps our details were being passed on to the CIA and right now someone was running a check on us in Langley, Virginia? Sometimes it does not do to allow the mind to run wild, especially when you are flying through fiercely contested airspace over an ocean far from home. But the Ukrainian controllers were as helpful and efficient as everywhere else and we chuntered on uneventfully.

After a couple of hours, we were turned left and passed on with no ado to their Russian colleagues for the last hour of our flight, which was in uncontestedly Russian airspace. There was a lot of local traffic on the Russian frequency and it felt as if the Ukrainian airspace had been a wormhole, a vortex, through which we had been transported into a completely different universe. Ankara Control, Sofia Control, Burgas airport, Europe: all now felt unimaginably distant.

Before long, we could see the Russian coast ahead and, a few miles beyond, the airport, a little way north of Anapa town. As we came down final approach we could see two lime green S7 Airlines Boeing 737s parked in front of the terminal and, closer to us, adrift in the concrete wilderness of an enormous ramp, three old-style Russian turboprop airliners, the ones with the quaint glass nose bowl for the navigator and a samovar of tea always on the boil in the aisle. (The last bit may not quite be true, even if it should be.)

The wheels squeaked onto the runway and, as we turned off after the Follow Me car at the designated exit, we may have turned to each other with a quiet, satisfied smile and firmly and proudly shaken hands on the achievement. Or, we may have exclaimed in disbelief: “F**k, we’re in Russia!” One or the other.

The Follow Me car took us to a lonely patch of concrete that looked like all the other patches of concrete, placed some red metal chocks aside each of the wheels, devices so enormous that they could have immobilised a Soyuz, and then drove off, leaving us alone. We noticed a movement over our left shoulders. From the direction of the turboprops, a couple of hundred metres away, three young women in 1960s-style air stewardess uniforms were striding towards us with bags over their shoulders. “How nice,” we thought. “The stewardesses from those turboprops are coming over to greet the gallant foreign aviators.”

But as they approached, it became apparent their mission was not to place the Russian equivalent of leis around our necks (perhaps a chain of vodka minis), but an altogether less frivolous one. They were the immigration officers and they wanted our passports. How did we know? From a good twenty yards off one of them started shouting “Passport! Gen Dec! Passport! Gen Dec!” over and over. We were still in the cockpit, still in our immersion suits, and tumbled out as they continued to bark: “Passport! Gen Dec! Passport! Gen Dec!” We struggled out of the immersion suits, furnished the required documents, which appeared to be in order, and they calmed down, eventually becoming as giggly as they had been shouty.

They finally left us in the charge of the customs officer, who had ambled up by this time. He was a pleasant young fellow of about thirty, but perturbed. He kept scrutinising my passport and the aircraft registration papers, looking from one to the other, repeating the same phrase and shaking his head sadly: “это не стандартный случай.” (eto ne standartnyy sluchay) “This is not a standard case.”

It was clear by now that foreign light aircraft asking for a month’s permission to cross Russia and then to depart it eight time zones and 5000 nautical miles away were not a frequent occurrence in Anapa. We felt like something of a local sensation and we had only been in the country for ten minutes. As it was now 4pm on Saturday afternoon, we agreed that we would reconvene with his boss at the customs office on the far side of the airport on Monday morning to sort out this “non-standard’ case. In the meantime, though we could not proceed on our trip, we were free to go into Anapa.

This was fortunate, as by now we were badly in need of a meal and some beer, so we hired a car and drove into town to a cheap hotel we had booked on booking.com. Anapa is a pleasant enough little seaside town, but congested, a bit tacky and its limited riviera charms would not set the heart of a Kiwi or an Australian ablaze. It takes the recollection that these few hundred miles of the Black Sea coast are the only warm water access this immense nation possesses, to understand why direct flights land here from as far away as the frozen city of Yakutsk, over 3000nm away in the Russian Far East.

Sunday was spent at leisure in Anapa, strolling around, eating bliny in a small café at the port, and remarking to each other at frequent intervals, “Hey, we’re in Russia” and “Can you believe we’re actually in Russia?” Into this triumphant interlude, however, kept intruding the gnawing uncertainty of what Monday would bring. We reassured ourselves that there were only two likely outcomes: they would allow us to proceed on our way or they would send us back the way we had come. And, while one outcome was more palatable than the other, we could live with either. The third potential outcome – impounding the aircraft and throwing us in the clink – seemed unlikely as it would mean too much hassle for them, what with the consequent diplomatic uproar, questions from their superiors, recriminations as to who had authorised this outrage and so on. We had faith that we were a problem they would ultimately wish to be rid of, and so it proved.

The problem, as we discovered on Monday, was simple and yet, to the bureaucratic mind, not so simple. I am not a US citizen (I am an ‘alien’ in the charming vernacular of that country) and so I cannot legally own a US aircraft. N185MW is therefore owned by a UK based trust, administered by a US citizen, of which I am the beneficial nominee. It is under the name of this trust – Southern Aircraft Consultancy Ltd – that the aircraft is registered, not my name. I produced a letter from the trust authorising me to operate the aircraft worldwide. I produced the purchase invoice and the trust agreement. All of these were in English and while my schoolboy Russian of forty years before (“давай купим мороженое!” – davay kupim morozhenoye – “Let’s buy some ice cream!”) had proved sufficient for a Sunday afternoon in Anapa, it was not sufficient to explain the intricacies of Federal US law as it relates to aircraft ownership by non-US citizens.

Evgeny eventually managed to explain it all to them over the phone, but the documents were going to need to be translated into Russian before they would think of issuing a customs carnet. Until then, the aircraft was impounded. It was now after lunch on Monday and Evgeny thought he could probably get the documents translated in Moscow by the end of the day on Tuesday, which meant nothing was going to happen until Wednesday at the earliest.

We refuelled the aircraft that afternoon from the two 200 litre drums which were delivered by truck from the city of Krasnodar, the first of our hand-pumping exercises since Schefferville in far off Labrador some weeks before. Our concerns about fuel quality in Russia were instantly allayed. The drums were brand new, immaculately labelled and, connoisseurs of AvGas that we are, smelled and looked absolutely right. This was pukka 100LL alright.

The next day, Tuesday, we decided to drive to the Crimea, which is about an hour and a half to the West across the newly built (2018) and phenomenal Kerch Bridge, the only decent piece of infrastructure we came across in the region. Lunch was in a pleasant café in the city of Kerch, quite a picturesque town, but down at heel. Tom bought a pair of jeans in a small shop, run by a woman who clearly loves jeans and kept telling us so: “Я люблю джинсы!” (Ya lyublyu dzhinsy!) “I love jeans!” And, to be fair, she did have a terrific selection. If you’re ever in Kerch and you find you need jeans, you’re in luck.

On the way back we stopped at the tiny beach resort of Veselovka on a small sand spit which holds back a large brackish lagoon. It didn’t take much to imagine the generations of Soviet workers who had once holidayed here. Apart from the endless Russian technopop blaring out all down the beach, instead of patriotic or schmaltzy folk songs, it didn’t look like much had changed.

Wednesday dawned and the translations of the trust and purchase agreements came through from Moscow. We trooped back to the customs office at the airport, past the indolent guard at the door with his oversized Russian peaked cap (why is that, anyway?). He looked like he was keen to kick us in the kidneys. The two senior customs officers were pleasant enough, but obviously more bored with this whole affair than they had been two days before; a good sign.

Before long, we were stepping out of the office with a newly minted Russian customs carnet covering our beloved N185MW until the end of our visa. The problem was we had already been five days late into Russia and now had lost another five days, giving us only twenty days to get through Russia before our visa expired. We had a lot we wanted to do, it was September and that meant we were heading into the uncertain weather of a Siberian autumn. We were almost certainly going to need to extend the visa and the customs carnet, but that was a problem for another time. For now, though, we could think only about the next day’s destination: Stalingrad!

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2021 edition of Approach Magazine, the dedicated magazine of AOPA NZ, which is published quarterly.